I Struggle to Digest Food Now: The Overwhelming Burden of Running a Football Club

Pep Guardiola’s list of symptoms is extensive and troubling. He struggles with sleep. In the evenings, he can only manage light meals. Some days, he skips eating altogether. Reading is a challenge; his mind often drifts. At times, he experiences profound loneliness. The situation can escalate to manifest physical issues: episodes of back pain, skin breakouts.

These struggles aren’t confined to moments like those when the Manchester City manager feels ensnared, as his team endures a slump he has tried fruitlessly to remedy for two months. By his own acknowledgment, this is his constant state. Guardiola finds it hard to sleep, eat, or even relax, regardless of how well things are going at work.

Manel Estiarte, one of Guardiola’s most trusted allies, once referred to it as the “Law of 32 minutes.” Estiarte had spent enough time with Guardiola to pinpoint exactly how long his friend could discuss another topic — any topic — before his thoughts circled back to football.

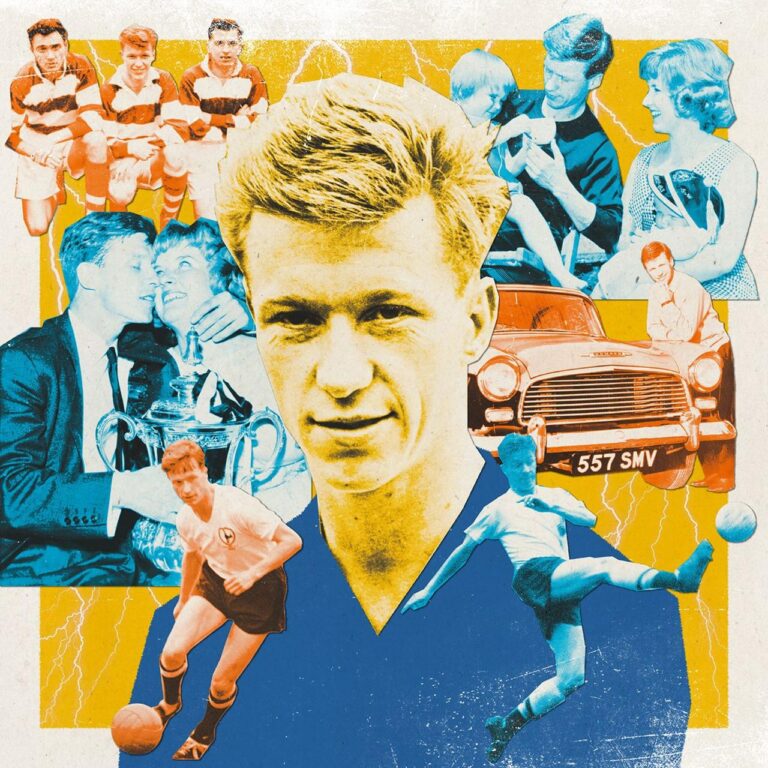

This image has been assimilated into Guardiola’s narrative. He is seen as the obsessive genius, his thoughts perpetually buzzing and alive, with a mind that seems always poised for action. His teams at Barcelona, Bayern Munich, and City are embodiments of his ideas, beautifully realized. His brilliance has only been confined by the scope of his imagination.

However, the toll of that dedication has become evident in recent months. As City’s form declined, Guardiola has given at least two notably grim interviews: first to the Spanish chef Dani Garcia, and then to his former teammate and enduring friend, Luca Toni on Prime Video Sport. To Garcia, he described the “loneliness of the football manager,” noting that in defeat, there is “no consolation” once you “close that bedroom door and turn off the light.”

With Toni, he expressed how his health has been affected: the skin issues he has grappled with for “two (or) three years,” alongside his eating and sleeping difficulties. “I don’t digest food properly now,” he remarked, suggesting that this metabolic change might be permanent. Sometimes, he feels as though he “loses his mind.”

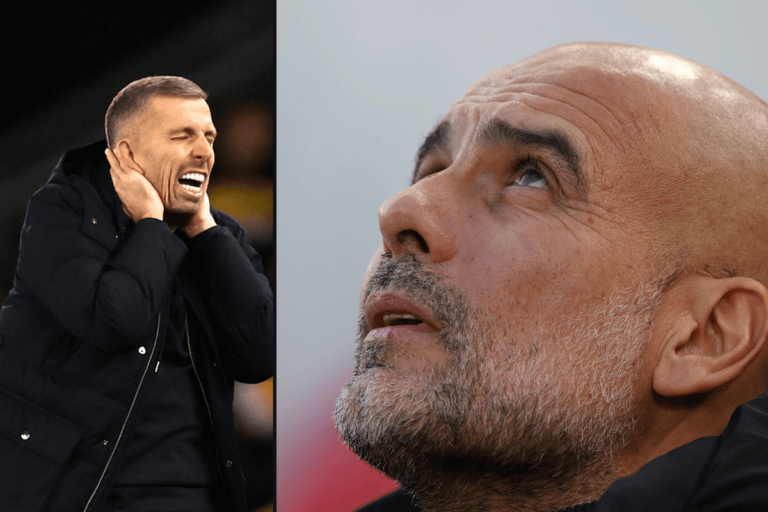

Guardiola during Manchester City’s 2-2 draw against Crystal Palace this month (Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

His bluntness regarding these issues — and the fact he claimed to be “fine” only days later — might stem from the familiarity of the situation. He had trouble sleeping during his last year at Barcelona. In 2019, when City wrested the Premier League title from Liverpool, he had long stopped eating on matchdays. In 2018, he stated at the University of Liverpool that he couldn’t read books to unwind because “I start reading and before I know it I am reading about Jurgen Klopp.”

It may also reflect a standard experience for those in his line of work. Management has always come with its stresses. Many of Guardiola’s renowned predecessors — Bill Shankly, Arrigo Sacchi — either resigned or stepped back due to the strain of the role. The individual he deemed his fiercest rival, Klopp, took a break from Liverpool for related reasons.

This profession has often been suited to those who are singularly focused, driven, and fanatical. Yet, even among those who repeatedly choose this path, it is widely acknowledged that it appears exceedingly detrimental to one's wellbeing.

Richie Wellens, the Leyton Orient manager, shared with The Athletic this year that the stress of management has even impacted his ability to grow facial hair; Nathan Jones, who previously managed Stoke City and Southampton, would bite his nails to the point of drawing blood. Back in 2002, some preliminary studies indicated that managers experienced such significant stress during matches that they suffered irregular heartbeats.

“I definitely didn’t feel healthy at the end of my time at Chelsea,” Emma Hayes, currently heading the United States’ women’s team, remarked last month. “I don’t want to say it’s pressure. I just think it’s the stress, the toll it took on me.”

It's easy to conclude that this is unavoidable, given the vastness of the football industry, the financial stakes, and the incessant media scrutiny. However, in some respects, management should be less stressful now.

Hayes walks away after an altercation with the then-Arsenal Women manager Jonas Eidevall in March (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

Many clubs have alleviated the burden of management: technical or sporting directors manage recruitment; chief executives oversee contract negotiations; entire departments are dedicated to game analysis and scouting coordination. Shankly couldn’t reach out to a psychologist, specialist set-piece coach, or nutritionist.

Yet this restructuring hasn't appeared to lessen management’s demands. Ange Postecoglou, the Tottenham Hotspur manager, may have been slightly exaggerating when he claimed it was the “hardest job in any walk of life,” but following his logic wasn’t difficult.

“You can say politics, but this is harder,” he said. “The tenure and longevity of this role now means you go into it and very few are going to come out without any scars.” When asked how he would compare it to being the prime minister of a real country, he replied: “How many times does he have an election? I have one every weekend, mate. We have an election, and we either get voted in or out.”

This can be partly explained by the fact that, while football has delegated responsibilities behind the scenes, it has not done so in front of the cameras. The manager, especially in England, usually remains the club's sole public representative.

“They have to comment on everything,” Michael Caulfield, a sports psychologist who collaborates with Brentford and other clubs, stated on BBC Radio 5 Live last week. “From Covid to Brexit to anything you care to mention: potholes, traffic, the price of hamburgers. Football is not good at sharing that workload. It is too much for one person.”

Brighton head coach Fabian Hurzeler at his unveiling in July (Steven Paston/PA Images via Getty Images)

This outdated model has its practical advantages — as one club executive privately noted, it simplifies matters when certain questions can be directed at a manager who can genuinely say they do not have the answer — but it fosters the impression that the complete responsibility for the club's wellbeing rests on a single individual.

Notably, Fabian Hurzeler — the 31-year-old head coach at Brighton — does not indulge in TV or movies but instead reads books on “mindset.”

“What is the mindset from high-performance people? People like Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg. I like to understand how they behave, how they get so successful,” he said this season. Hurzeler’s reading choices are his own affair, but they hardly suggest relaxation.

In fact, many Premier League managers find it hard to articulate how they unwind. A good number enjoy exercising — many are particularly fond of padel, with Hurzeler among those advocating for his club to build a court at their training center — yet genuine interests outside the game seem limited.

Nuno Espirito Santo enjoys looking out the window at the River Trent. The night before his unexpected dismissal from Wolves, Gary O’Neil set aside time to finish watching the movie Wonka with his children, acknowledging the importance of “switching the brain off.” Yet, he was acutely aware of how much time he had left. “I will try to switch off for an hour and six minutes,” he mentioned.

The River Trent running by Forest’s ground. Their manager Nuno finds solace in watching the river (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

Caulfield characterized Thomas Frank, his head coach at Brentford, as being unusually well-adjusted for a manager — he plays padel (naturally), skis, spends time at his home in Spain, and maintains friendships unrelated to football — but even he concedes that his “brain is thinking about the next game” almost constantly during the season.

He occasionally watches interior design shows with his wife, but only because she “forces” him to do so. Roberto Martinez, currently managing Portugal, mentioned in an interview with The Telegraph in 2015 that he designed his living room to accommodate one sofa and two televisions: one for his wife to enjoy regular programming, the other for him to catch up on football matches.

None of this is healthy. The League Managers Association, which advocates for current and former managers in England, has published a manual encouraging its members to seek a work-life balance; it stresses that they cannot perform optimally if they are exhausted and drained.

“That is the biggest problem,” Caulfield commented. “Football is exhausting. That culture of ‘be there seven days a week’ needs to change. Managers must manage their energy as much as their players. We aren’t made to work seven days a week, 24 hours a day, under such pressure and scrutiny.”

Guardiola is perhaps a testament to that. The symptoms of being a manager are indeed more pronounced now. He suffers more acutely following defeats. Yet he has grappled with these issues for years. “I think stopping would do me good,” he confided to Garcia, the chef, in one of those stark interviews.

He is aware of this yet persists. Like many of his colleagues, he will continue to seek the challenge.

(Top photos: Getty Images)