Unveiling Football’s Most Perilous Pass

A tense, eager breath taken in, followed by applause that reflects a blend of subdued admiration and, above all, relief. On other occasions, it concludes with fans shaking their heads in confusion.

We're referring to the audience's response to — and I’m taking this phrase from a colleague who frequents Stamford Bridge — “the most perilous pass in football”.

This is the brief, vertical pass from the goalkeeper to — usually, but not exclusively — the midfield pivot, who receives it amid pressure, facing their own goal and situated close to their penalty area.

Exhibit A: Chelsea’s Robert Sanchez attempting, and failing, to pass to Moises Caicedo against Brighton earlier this season, leading to Carlos Baleba scoring.

What a season Carlos is having! 🔥 pic.twitter.com/D7qC37kvwb

— Brighton & Hove Albion (@OfficialBHAFC) September 29, 2024

Baleba experienced a role reversal against Fulham, with Alex Iwobi capitalizing on a misplaced pass from Brighton goalkeeper Bart Verbruggen.

Forcing the error. 👊 pic.twitter.com/g0Jmd2O2LN

— Fulham Football Club (@FulhamFC) December 6, 2024

As for Chelsea, they retaliated against Southampton, where Noni Madueke intercepted Joe Lumley’s pass (35 seconds onwards in the clip below) to Kyle Walker-Peters, setting up Christopher Nkunku for their second goal.

Tune into all of Wednesday night's action. 📺#CFC | #SOUCHE pic.twitter.com/zY3em5RMBA

— Chelsea FC (@ChelseaFC) December 5, 2024

Fulham? They were fortunate not to concede against Newcastle when Bernd Leno signaled a pass to Emile Smith Rowe, leaving Newcastle’s players in disbelief when Fabian Schar somehow failed to score.

Brentford experienced relief against Ipswich, who came dangerously close to serving up a goal on a platter to West Ham in October. A VAR offside decision saved Tottenham Hotspur’s Fraser Forster at Bournemouth, where goalkeeper Kepa Arrizabalaga was lucky that Gabriel Martinelli didn’t punish him for a careless pass against Arsenal, which is where Mads Hermansen passed Leicester and Harry Winks into a precarious situation (see below) in September.

Regarding Manchester United, the ghastly goal they conceded against Viktoria Plzen in the Europa League last week serves as another case in point.

The examples are plentiful and, in many respects, support those who ponder why so many teams persist in taking such risks when playing out from the back, particularly with this type of pass.

There are likely several reasons for this. First, on a broad level, coaches who adopt this strategy believe it is much more advantageous to attack in a controlled manner, maintaining possession through a combination of proven principles and practiced movements, even if it occasionally leads to mistakes, rather than taking a gamble and hoping for a fortunate outcome — this is how they perceive knocking longer balls forward.

Secondly — and this is something that becomes apparent when discussing some of the aforementioned incidents with coaches who advocate for this style of play — the issue arises in the execution of that bounce pass near the goal, encompassing decision-making, positioning, movement, and timing, rather than the pass itself.

Lastly, it’s inevitable that the breakdowns in these moments will receive far more scrutiny than successful sequences of play.

Before we delve into further examples, it’s important to note that some Premier League clubs — or perhaps ‘some Premier League managers and goalkeepers’ — show little willingness to engage in this risk-reward game. Goalkeepers at Bournemouth (Arrizabalaga strayed against Arsenal), Crystal Palace, Everton, Newcastle United, and Nottingham Forest tend to favor short sideways passes when building up play or resort to long passes.

Indeed, even when the No 6 drops deep to receive a vertical ball in space with no visible pressure, goalkeepers often decline to make the pass. Illustrated below is Nottingham Forest’s Danilo, arms raised, signaling for a ball he was never going to receive from goalkeeper Matz Sels.

Newcastle’s Nick Pope behaves similarly (Bruno Guimaraes is indicating that Sandro Tonali is open below)…

… as does Everton’s Jordan Pickford.

That said, Pickford unexpectedly deviated from the norm against Arsenal on Saturday. This led to a chaotic moment involving him and James Tarkowski, as the Everton goalkeeper mishandled a pass that the center-back struggled to control, prompting Martinelli to press. The reactions of the two Everton players afterwards told the whole story.

Now, let's explore some instances of play that emphasize the reward rather than just the risk, starting with Arsenal’s 1-1 draw with Chelsea in November.

Declan Rice is the focal player here. He positions himself behind Nicolas Jackson, on the opposite side to the unmarked player (William Saliba) he aims to connect with after Arsenal has drawn Chelsea’s press with a short goal kick.

Cole Palmer makes the usual run (curved) for any player leading the press in this scenario, attempting to force the ball to one direction. Jackson, meanwhile, is prepared to move to Gabriel if David Raya opts to return the pass.

Timing and synergy are crucial to what unfolds next. Rice waits until Palmer gets closer to Raya and then shifts to the blind side of Jackson to receive a delicate pass in front of him that…

… he can then play first time to Saliba, allowing Arsenal to escape.

This pattern will frequently appear at Arsenal and beyond.

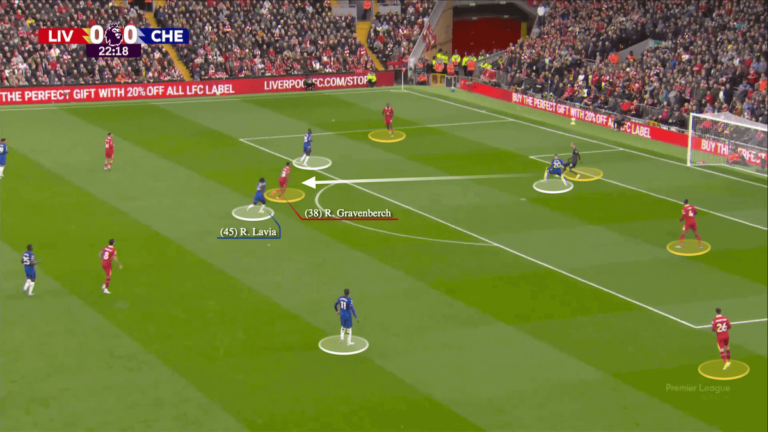

Below, we see an instance of Ryan Gravenberch executing a similar play for Liverpool on the season's opening day against Ipswich.

Gravenberch is particularly interesting to observe when receiving direct passes due to his remarkable skill in managing the ball under pressure while turning. In the image below, Chelsea’s Romeo Lavia is pressing him.

However, Caoimhin Kelleher’s pass is directed to the ‘safe side' (away from Lavia's direction), and Gravenberch excels at positioning his body between the opponent and the ball to shield and turn seamlessly.

Both Arsenal and Liverpool are not just maintaining possession in these instances but are also effectively taking opposing players out of the play while advancing their attack.

Consider this example of Manchester City advancing against Liverpool at Anfield in early December. The moment that initiates this sequence of play is noteworthy and encapsulates the modern game: Ruben Dias finds himself in a one-on-one against Luis Diaz, just 10 yards out, with nobody available in goal (Stefan Ortega is positioned at the corner of the six-yard box, out of the frame).

Once Dias passes to Ortega, Manuel Akanji recognizes he must connect with the City goalkeeper. Cody Gakpo, highlighted on the left, is already anticipating the play and readies to press Dias.

The expected action for Akanji — and the result during 99 times out of 100 — would be to pass to Dias.

Indeed, Mario Lemina did precisely that against Liverpool in September. Salah anticipated the move perfectly but, out of character for him, missed with his shot on an open goal.

However, Akanji scanned the situation before receiving from Ortega, and, with Dias also indicating where to play next, recognized the necessity and opportunity for a more forward-thinking pass to Kyle Walker.

As the City right-back advances, a line of four Liverpool players is effectively neutralized.

But that illustrates Arsenal, Liverpool, and Manchester City, I hear you thinking. What about clubs beyond the traditional ‘Big Six’?

Brentford presents a compelling case study, particularly regarding their evolution under Thomas Frank. The percentage of long passes from their goalkeepers has decreased by a third in under two years. Additionally, the bounce pass for building play has been frequently utilized this season, with the exception of a minor miscommunication against Ipswich that went unpunished and a slightly nervous episode during the first half against Chelsea on Sunday; overall, it has functioned exceedingly well.

The example below is from Brentford’s match against Villa, commencing with Ethan Pinnock passing a goal kick to Mark Flekken. Notably, Vitaly Janelt’s clean technique and game awareness shine through in these scenarios.

In the subsequent image, Janelt extends his right hand, advocating for calm and signaling to Flekken to hold on as Ollie Watkins begins to make his recognizable curved run. This sequence demands a lot from Flekken — or indeed any goalkeeper. It requires not just skill with their feet; they must remain composed, trust their teammates, and make intelligent choices in response to the opposition press.

As Watkins nears, Janelt makes his move, racing in pace and running off the back of John McGinn, who is focused on Flekken and Pinnock.

Youri Tielemans breaks free from Yehor Yarmoliuk and leaps, along with McGinn, to pressure Janelt. Nevertheless, Brentford's midfielder and Flekken execute their plan perfectly, and Nathan Collins is ‘out’.

Three Villa players have been bypassed as Collins surges forward and…

… shortly thereafter, Yoane Wissa possesses the ball within the Villa half, and Brentford begins a four-versus-four attack.

At first glance, one might conclude that the highlighted sequences of play appear relatively straightforward. In reality, these actions necessitate countless hours of practice on the training ground, as well as players equipped with both the technical prowess and mental resilience to manage the ball in such scenarios and alleviate crowd tension. This leads to a question fans frequently pose about their team: are our players skilled enough to execute this style?

Let’s examine some clips demonstrating where things take a turn for the worse.

The following clip is from Manchester United’s encounter with Tottenham in September. Diogo Dalot, acting in the role of an auxiliary No 6, receives a direct pass from Onana while turned away from the goal. Both United center-backs — Matthijs de Ligt and Lisandro Martinez — are positioned higher than expected in this scenario.

Typically, the pass made from the player occupying Dalot’s position would be a first-touch, executed with the left foot, given that Dejan Kulusevski is pressing. However, Dalot takes an additional touch to control the ball with his right foot…

… rotates his body entirely, and passes with his right foot, allowing Kulusevski to close in and potentially block the ball. This extra touch also enables Brennan Johnson to press Martinez more easily (albeit, Martinez's lack of depth exacerbates the situation).

In a moment of panic, Martinez helps the ball forward without much thought…

… resulting in Pedro Porro now launching an attack for Spurs.

Some coaches provide far more detailed instructions than others. They emphasize, for instance, the significance of goalkeepers receiving the ball in a neutral position, which prevents the pressing opponent from discerning which side to engage and also discourages goalkeepers from executing sweeping passes (think of that awkward Pickford ball to Tarkowski against Arsenal) to avoid the ball arriving with a bounce or spin.

In summary, merely completing a pass to a teammate is insufficient when playing against a press; it's about offering the receiver the best possible opportunity to execute their following action flawlessly — after all, a sequence of passes will often be necessary. It’s fascinating to hear Liverpool players discuss how their manager, Arne Slot, has interrupted training sessions over improperly directed passes that fail to reach the back foot of the receiving player.

The risk posed by a single careless pass is that it often triggers another mistake. In the next image, the Ipswich goalkeeper, Arijanet Muric, makes a risky play against Tottenham’s Dominic Solanke, utilizing the outside of his right foot. It’s high-risk and it succeeds, yet the pass isn’t forgiving for Sam Morsy to receive on the first touch, leading to a subsequent untidy pass…

… culminating in Dara O’Shea leaping to seize control of the ball, further provoking Spurs to increase their pressing.

Ipswich remains committed to building play from the back under Kieran McKenna, utilizing a multitude of straight passes that they typically execute efficiently — the montage below is from last Saturday's game against Wolves.

McKenna — and this is crucial for any coach aspiring to implement this approach — has taken the time to clarify his philosophy to Ipswich fans to help manage the anxiety that often arises in stadiums during these movements.

However, playing away proves to be more challenging, as visiting supporters relish moments akin to what Ipswich faced at West Ham earlier in the season.

The first detail that stands out when observing the forthcoming sequence is the setup. Prior to the goal kick, both of Ipswich’s defensive midfielders, Morsy and Kalvin Phillips, are marked closely from behind, signaling a potential red flag.

Morsy cannot approach the ball with any speed or on the blind side of an opponent. As for Phillips, his movement into the penalty area makes it more congested as he drops deep and brings Lucas Paqueta along with him.

In fact, Phillips nearly obstructs Morsy’s pass…

… which ultimately lands at Paqueta’s feet.

Amid the chaos in the Ipswich penalty area, O’Shea clears the ball off the line.

Speaking of congestion, there were 14 players (8 v 6) in a confined space when Southampton attempted to build play against Villa this month (see the image below). Southampton managed to evade danger this time, but they conceded against Liverpool in a similar circumstance, as did Chelsea.

Observing Southampton this season, it was evident that neither Lumley nor Alex McCarthy, who filled in for the injured Aaron Ramsdale, appeared capable of executing Russell Martin’s style of play at this level — and perhaps they weren’t the only ones.

Certainly, there are instances when the direct pass isn't feasible and the goalkeeper must adopt a more cautious strategy. Fulham’s Sander Berge is shown below signaling to Leno that he should bypass him and pass over the top of Brighton’s aggressive press.

A goalkeeper finding themselves in a state of indecision is likely the worst scenario, exemplified by Tottenham’s Guglielmo Vicario against Brentford (illustrated below). It appears as though Vicario is so conditioned to execute that straight pass (a central aspect of Spurs' build-up under their coach Ange Postecoglou) that he fails to identify an alternative. Fabio Carvalho took advantage of Vicario’s uncertainty, but commendably, the Spurs goalkeeper recovered quickly and prevented Bryan Mbeumo from scoring moments later.

Both Vicario and Forster, his backup, have had their share of narrow escapes this season, most recently at Bournemouth a couple of weeks ago, where Kulusevski seemed vulnerable after receiving a direct pass from Tyler Adams.

On Sunday, against Southampton, Spurs resumed this approach right from the kick-off.

Just four passes later, James Maddison found himself through on goal, taking his team 1-0 up.

The peril, Postecoglou and others would argue, is justified by the outcome.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Meech Robinson)