The Evolution of Premier League Stadiums Over the Last 40 Years

Soaring above a segment of the River Thames recognizable to millions due to the annual Boat Race, Fulham’s new Riverside Stand is already making its mark on the London skyline.

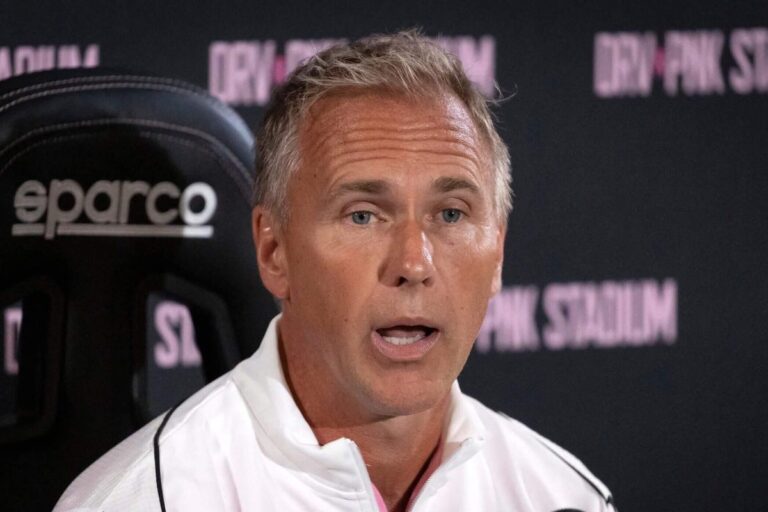

Who believes this? Simon Inglis, the leading stadium authority in the UK and the author of the pivotal book on the topic, The Football Grounds of England and Wales, first published in 1983.

“I genuinely believe it’s the finest football stand of the 21st century,” he states. “You immediately think, ‘Wow, an architect has been involved in this.’ I appreciate how the roof extends out, almost like a gigantic wing. And how it’s elegantly designed at the rear, close to the river.

“It has the potential to become a true iconic landmark in London. Simultaneously, I would argue that it has a bold and quite American aesthetic. The very glossy black cladding could be perceived as resembling a funeral home.

“Nonetheless, it harmonizes with Fulham, which plays in black and white.”

Fulham’s new Riverside Stand – a landmark for London? (Alex Davidson/Getty Images)

Inglis also notes approval for how the £100 million development, set to fully open in 2025, has enhanced accessibility along the north bank of the river in west London. The public can now stroll behind the new stand, a significant improvement. Previously, those on the ‘Thames Path’ heading from Hammersmith had to divert inland via Stevenage Road before returning to the riverside in Bishop’s Park.

“This was one of the great innovations they implemented at Arsenal,” he adds, referring to the Emirates Stadium that opened in 2006. “Instead of creating an impermeable ring open solely on match days, vistas and pathways were opened that serve a purpose seven days a week.

“This way, the stadium becomes integrated into the community.”

While Fulham’s new Riverside Stand may not appeal to all, some might prefer a more traditional aesthetic, such as the Archibald Leitch-designed stand, alongside the adjoining Craven Cottage, located directly across from Fulham’s pitch from this stunning new addition to the capital.

There’s also Liverpool’s reconstructed Kop or the single-tier South Stand at Tottenham Hotspur’s relatively new home, designed to mirror the famous Yellow Wall at Borussia Dortmund.

Tottenham’s new stadium opened in 2019 (Tottenham Hotspur FC/Getty Images)

Regardless of personal taste, there's no denying Inglis’ reputation as the leading authority on the evolution of stadium design.

Having virtually pioneered the genre with his influential book, he later played a significant role in shaping football’s response to the safety reforms mandated after the Hillsborough tragedy, which claimed 97 lives.

Inglis was the only individual to sit on both the Football Stadia Advisory Council and the Football Licensing Authority committees and also served as editor of The Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds, commonly referred to as The Green Guide, which has essentially become the safety standard for clubs.

This reflects a remarkable resume for a man who initially viewed combining his passions for football and architecture as merely a side project amidst a broader writing career that included contributions to The Guardian and Radio Times.

“Making a living out of football grounds all these years later still seems a bit peculiar to me,” he remarks, being a lifelong Aston Villa supporter. “I often compare myself to an actor who secured a minor role in EastEnders but is forever remembered for that, irrespective of whatever else they accomplish in their career.

“I’ll still be recognized as the person who authored the ‘Football Grounds’ book.”

A selection of Simon Inglis’ stadium-related work (Richard Sutcliffe)

Inglis’ keen attention to detail and talent for uncovering facts that had been buried for years, combined with a writing style that transformed what could have been a dry subject of cantilevered stands and red-brick facades into something engaging, turned the 1983 book into a classic.

Having documented a world that was, unbeknownst to him, on the brink of extinction, Inglis went on to write two more editions in 1987 and 1996, creating a series that captures the transition from years of neglect to the construction surge prompted by the Taylor Report following the Hillsborough disaster.

He also elevated Leitch, a once-overlooked Scottish engineer responsible for nearly 30 football grounds in the early 20th century, to a cult status, with two of his stands — Fulham’s Stevenage Road and the South Stand at Ibrox — later being granted listed status.

In the interim between the first and second editions, the 1985 Valley Parade fire, which resulted in 56 fatalities and over 200 serious injuries as Bradford City’s wooden main stand was engulfed in flames, further underscored the urgent need for reform.

Suddenly, what was once a niche topic turned into a pressing issue, with Inglis called as a witness to the Popplewell Inquiry that was later extended to address the Heysel disaster, during which 39 Juventus supporters were killed merely three weeks after Bradford.

Ibrox, south stand nearside, as depicted in 1960 (Daily Record/Getty Images)

“Most clubs turned their backs on me,” he recalls regarding the extensive 7,000-mile research expedition for the first edition of ‘Football Grounds’, which included countless hours scouring local newspaper archives in public libraries.

“I’d sit in a waiting room for two hours to meet a club secretary, who would greet me with, ‘So, what’s this all about?’ I was disheartened to discover how little the people managing clubs understood about football ground design and how little attention they paid to it.

“They viewed architects as a predatory species, poised to exploit their profits. Additionally, fans at that time weren’t demanding more, despite dwindling attendances.

“Football was in a grim state throughout the Eighties.”

With final touches underway at Everton’s striking new venue on the Merseyside waterfront, and the ongoing discussions surrounding the future of Old Trafford, it's evident that football stadium design has evolved significantly.

The first wave of ground developments favored huge, sweeping terraces as they were cost-effective and could accommodate the largest number of attendees. Facilities were minimal, with even the best grounds, such as Wembley, resembling nothing more than a concrete bowl when it opened in 1923.

Young Everton supporters take position on the terraces at Goodison Park (Liverpool Echo/Getty Images)

Eventually, amenities like toilets and concourses for purchasing food or drinks became standard, along with rooves to shelter fans from rain. However, this was the extent of improvement during Inglis's early-Eighties explorations around grounds typically constrained by housing and industry, established in a past era when fans visited stadiums on foot.

“Other than Villa Park’s main stand (Trinity Road),” he comments, “I wasn’t observing any remarkable architecture. There were occasional interesting features, such as a new stand in Coventry.

“Overall, it was the architecture of neglect and practicality. There was little to appreciate visually, yet stepping into these grounds transported you to a completely different realm.”

Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge, depicted in 1988 (Ben Radford/Getty Images)

These grand, historic football grounds may have evoked transformative experiences but posed significant risks, as evidenced by a somber list of calamities, including 33 fans crushed at Bolton Wanderers in 1946 and an additional 66 at Ibrox 25 years later.

British football’s death toll could have been much higher with numerous near disasters, such as more than 30 fans hospitalized at Leeds United’s Elland Road after a crush barrier failed in 1967.

It was not until the 1989 tragedy at Hillsborough, where eight years earlier, 38 Tottenham fans suffered from a range of injuries including broken arms and ribs in a crush during another FA Cup semi-final, that significant changes began to occur.

“Prior to 1990, there was no stadium industry,” Inglis comments. “No platform for sharing best practices. Everything was haphazard, with most clubs employing local builders or architects or asking a chairman's friend to handle the design work.

“Breaking away from that pattern was essential. We sustained a British approach to the issue, resulting in functional stadiums in suitable areas.

“We didn’t adopt the American model (by constructing out-of-town stadiums) or even the Italian model from the 1990 World Cup, which involved enlisting signature architects to create stadiums that would impress architectural critics but not necessarily be practical for users.”

Derby County’s Baseball Ground, located between industry and housing (English Heritage/Getty Images)

Inglis contributed to English football's progression from the depths of Hillsborough. He collaborated with architects, engineers, civil servants, and safety experts, along with emergency services, on the two committees established to drive the necessary change, ultimately compiling the revised version of the Green Guide, initially published after the Ibrox tragedy of 1971 that resulted in 66 deaths.

By the time the Guide was published under his editorship for the first time in 1997, terraces had almost entirely vanished from the top two divisions, despite his initial reservations.

“The issue lay not with terraces themselves but rather with safety management and design,” he explains. “I lost that debate, yet I comprehend the rationales behind the decision. Though my perspective wasn't unique, I was, within that circle, the only actual fan. The rest were former police or fire personnel.

“It was an enlightening experience for me. I learned a great deal and developed immense respect for those in those roles. Each of them had undergone significant trauma stemming from Hillsborough.

“Their entire approach to ground safety was re-evaluated. Being part of that transformation was truly remarkable. I felt a genuine responsibility — along with many others, particularly forward-thinking architects and engineers — to ensure Hillsborough wasn't just another disaster but the last one.”

Change materialized swiftly following the Taylor Report's release a year after the disaster, with a deadline set for phasing out terracing in the top two divisions by August 1994. Clubs in the third and fourth tiers were also expected to comply within five years.

Any team elevated to the second tier within that timeframe would have three years to adapt, rendering Fulham the last club retaining old-style terracing in the Premier League, having climbed from the third tier in 1999 to the top flight in 2001.

The all-standing Putney End at Craven Cottage, depicted in 2001 (Mark Leech/Getty Images)

This directive from Taylor to transition towards all-seater stadiums was subsequently diluted, with clubs in the leagues that are now recognized as Leagues One and Two exempt, albeit under the provision that any remaining terraces had to be upgraded to the highest standards by 1999.

Further alterations ensued, including the Football League implementing minimum ground criteria in terms of capacity (6,000) and seating (1,000), applicable to existing members and clubs promoted from the Conference.

However, it was the stipulation for all-seater venues that had the most significant repercussions, as iconic terraces like Manchester United’s Stretford End (1992) and Liverpool’s Kop (1994) were demolished. In their stead emerged new stands with significantly upgraded facilities, reflecting a shift in atmosphere that left fans advocating for a return to safe standing areas, which have now become commonplace in the Premier League and Championship.

Numerous clubs interpreted the Taylor Report as the signal to start anew, with a dozen clubs including Millwall, Sunderland, and Derby County establishing new venues between 1993 and 1999.

Some, like Huddersfield Town’s McAlpine Stadium, garnered acclaim for their design, while others took a more utilitarian path.

Workmen at Huddersfield’s McAlpine Stadium in 1994 (Huddersfield Examiner/Getty Images)

Inglis notes: “For the British approach to lean towards a more subtle and functional style, I understood. However, I also hoped we would improve at it. Which, indeed, has occurred. To me, The Emirates was probably the first exceptional club stadium constructed in this nation since the early 20th century.

“Just as Hampden Park, Celtic, Rangers, and subsequently Old Trafford created a template for the prior century, Arsenal, Tottenham, and a myriad of international stadiums now present a scenario where a stadium can hold the marketing allure of a cathedral. I never anticipated witnessing this in my lifetime.”

Looking ahead, once Everton’s new ground opens in 2025, Old Trafford will be the next significant UK stadium project on the horizon. Manchester United must determine whether to renovate and expand the current facility or start afresh on adjacent land.

A proposed capacity of 100,000 has been discussed for a venture that could reach up to £2 billion, with United co-owner Sir Jim Ratcliffe advocating for governmental financial support for a ‘Wembley of the North’-styled national stadium.

Inglis speculates: “I’m confident they will execute a remarkable job at Old Trafford, although I personally would wager that it won’t reach 100,000. There is an unprecedented escalation in costs, maintenance, and a host of issues associated with increasing capacity from 80,000 to 90,000 and certainly to 100,000.

“You’ll end up either too distanced from the pitch or situated too high.

Old Trafford has a leaky roof – Manchester United is considering a rebuild (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

“Moreover, there is a substantial difference in managing the attendance of 100,000 versus 75,000 on match days. The success of Wembley isn't merely due to its uniqueness as a stadium. It’s largely a result of Wembley Park's status as a significant transportation hub in north-west London.

“Wembley Park Station's capacity was approximately 35,000 per hour the last time I checked. Constructing something similar at Old Trafford would be an immense task. The infrastructure surrounding roads and rail must be significantly upgraded, which entails millions in expenses.

“One reason Wembley emerged victorious over other bids to become the national stadium in the late Nineties (when I acted as a consultant for the project) is the existing transportation infrastructure surrounding Wembley.

“London is unrivaled by any city worldwide, save maybe Melbourne, in terms of available sporting venues. Yet, Manchester is thriving and already has a superlative infrastructure with the Etihad, Old Trafford, and the cricket ground.

“I’m skeptical that United will actually achieve 100,000. However, I will assert that if any stadium in this country is to reach that capacity, it will likely be in Manchester.”

(Top photo: Stamford Bridge in 1989 – Mark Leech/Offside/Getty Images)